An Enigma: Transmission Of Epidemic Influenza (part 1)

I attempt to shed light on the riddle that is seasonal influenza using my favourite bag of spanners. Today I turn back the clock on a few previous articles

Seasonal influenza and those perpetually mutating strains used to make sense to me as a greenhorn postgrad neurobiologist attempting to gain a PhD; but then I started asking very simple questions and answers were not forthcoming. Questions such as: how does a virus that is reliant on human-to-human transmission survive when humans are not transmitting? Or: where do all those strains live when they are not partying? Or: how come only one strain expresses itself at a time when this animal loves to mutate like there’s no tomorrow?

These are not questions you ask in polite company; such as the common room of your department when greenhorns and laureates alike are fighting for control of the kettle and grumbling over what biscuits have been left by biscuit-munching undergrads that came out of the first lecture early. Ask those sorts of questions at the wrong time in the wrong place and you’ll get snorted at… or someone will peer over their glasses down at the end of their long nose.

These days there is a palpable trend against all manner of ‘citizen science’, and a rather effective one that goes along the lines of you’re not sufficiently qualified to ask these questions. I wouldn’t mind this as much if the experts would then go on to explain the situation and educate us all; but they don’t do that. They float away on a raft of clandestine knowledge.

Someone courageous (and qualified) enough to ask these questions, and more besides, was R. Edgar Hope-Simpson F.R.C.G.P., whose seminal work The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza (Plenum Press, 1992) was purchased by my good self almost two years ago to the very day. That copy cost me deep in the purse, at £97.43, and I gather it is now retailing at £117.79. That’s a lot of gin so you might surmise there would be very good reason for me doing so!

The reason came in the form of a rather productive Zoom meeting with some movers and shakers in the world of COVID truth; the book being recommended bedtime reading by someone who knows their shallots as well as their onions. And read it at bedtime I did, for I could not put it down; my bed also being a secret haven for uninterrupted thought. Here’s the Amazon blurby blurb:

Mankind has always been fascinated by "origins," and biologists are no exception. Darwin is our most famous example. What is the origin of mankind, of species, of infectious diseases? In the last few years we have seen the emergence and spread of some apparently "new" viruses, such as HIV -1 and the virus causing bovine spongiform encephalomyelopathy. But are these, in fact, entirely new agents, or mutated forms of "old" viruses that have evolved along with us for eons? Edgar Hope-Simpson could not have written this book at a more opportune moment. He is a firm believer in gradual evolution, rather than the sudden arrival of new agents. I suspect that he would also have a naturalist's Darwinian approach for the origin of AIDS. It has been a source of some amazement to me over the years how even the most innovative scientists conform to a current hypothesis. Pioneer thinking comes more easily to persons outside the scientific mainstream. Edgar Hope Simpson has always struck me as a modem-day naturalist of the classic style, observant and perhaps a little maverick in line of thought. Certainly, the central hypothesis propounded in this book will be controversial to many scientists. From his unique citadel, the Epidemiological Research Unit in Cirencester, he has carefully re-examined mortality data from old records as well as new.

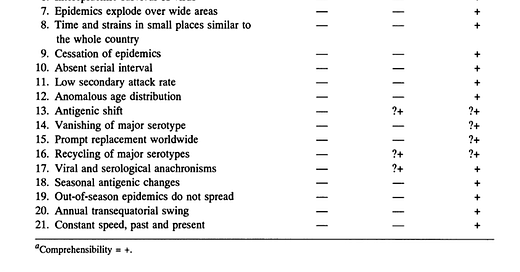

That doesn’t tell you very much, so let’s have a squizz at table 18.2 on page 235 that usefully summarises all of the problematic issues that Hope-Simpson chews over in the preceding pages:

That’s quite a table isn’t it? There ain’t just a few odd things that don’t make sense when you sit down and think but a whole big bunch of over-ripe bananas. I’m not an epidemiologist and I don’t have much time to devote to analysis these days so I’m not at liberty to explain all 21 ‘problems’ in full; besides which there is a magnificent hardback book you can go and purchase (and a few freebie PDFs hanging about the internet) and digest at your leisure.

The Big Picture

What I want people to take away from this is not the detail but the big picture; and this big picture indicates something is very wrong indeed with the notion of human-to-human transmission of that which we are calling influenza. That is to say it sure looks likes there ain’t any contagion aspect. Folk get flu-sick during the winter for sure, and they sometimes get sick in groups and localities, but the evidence mulled over at length by Hope-Simpson strongly suggests that flu-sick folk are not infecting each other. This is not something the establishment are keen to admit because bang would go billions in income from countermeasures, annual vaccines and all the rest. Lockdowns schmockdowns. If influenza A or B doesn’t, and cannot, transmit via snot and aerosol then what of their fashionable cousin that goes by the name of SARS-COV-2? Exactly. And what is most encouraging to see are those learned voices asking just what it was that was supposed to be circulating other than propaganda designed to maximise gene therapy uptake, early death and a much-needed boost for big pharma share prices.

Grumpy Mule

As I sip my Grumpy Mule I can’t help myself from mulling on the last ‘problem’: constant speed, past and present. It is a little known fact that influenza spreads with the same speed today as it did prior to invention of the steam engine. Forget air travel, train lines, the subway, expressways, e-scooters and crowded shopping malls: they haven’t made the slightest bit of difference to the rate at which influenza will travel through the population. If that doesn’t strike folk as mightily odd then we might as well watch game shows all day long and be done with it.

Not covered in table 18.2 is the peculiar observation of isolated influenza outbreaks on board turn of the century vessels that have been sailing in isolation for months on end. From out of the blue a bunch of crew go down sick all at once, with the remainder being unaffected. We have leather-bound ships’ logs (legal documents, I gather) to thank for that. An airborne virus might explain this but then again there are many reports of simultaneous outbreaks at such distance that even the wind cannot hope conquer! A mystery indeed.

The New Concept

The keen will spot the phrase “the new concept” in the table title and may well ponder, as I did. Hope-Simpson chews the fat at length on a daring new proposition; and the good man is keen to draw attention to problems and limitations even with his favoured hypothesis, as he should. And what is that favoured hypothesis, I hear you ask? Well, to put it into the words of one sentence: there ain’t any contagious (i.e. human-to-human) transmission of any kind. Instead, all of the influenza strains and their future offspring are already present in the human species, and have been thus since before the last ice age. All that happens is that something external and somewhat environmental comes along to trigger a latent nasty whose globe time has come. Hope-Simpson doesn’t exactly express what that external trigger actually is, but feels it is something to do with the Earth’s axial tilt, the seasons and solar exposure.

Some may pounce on this and declare a win for terrain theory. It kinda looks that way (and I have yet to find a satisfactory model based in germ theory that explains all of the observed problematic phenomena even if we resort to bugs bouncing between species); but this ain’t just terrain theory, and it ain’t just germ theory: I shall call it Germain Theory (see what I did there?). This being the case there’s one darn awkward issue for the ‘New Concept’ that could be called the elephant in the room: the many strains of influenza and their potential future offspring must somehow all be perpetually hiding in the human gene pool… and avoiding detection. H’mmm…

Homework

Back in January 2023 I found this offering a tad too Emperor’s New Clothes and rather bewildering and so, after reading every last word of Hope-Simpson’s captivating book, I embarked on some analysis of my very own to see what I could see. This work is enshrined in the following five articles that I am going to set for your homework. I suggest you don’t skimp on this because I’ll proceed with the current series on the understanding that subscribers will have digested every scrap of historic contents. Think of these as the soup course followed by a fish course, followed by a cleansing mint sorbet:

The singularly critical premise underpinning these five illuminating articles is that deaths from pneumonia and/or influenza offer up an excellent proxy for flu outbreaks. Whilst this is a rather reasonable assumption anybody familiar with my work will realise that counting deaths by cause of death isn’t at all straightforward. Not only is it not straightforward but we have the WHO interfering with how we Brits go about counting those counts. Sound familiar?

This is where my spanners came to the rescue and I ended by furnishing a corrected time series for pneumonia and influenza deaths for England & Wales for the period 1920 – 2022; this graphic being supported by the following final and rather brazen statement:

So there we have it – a two part series inspired by my grapple with La Grippe that reveals just what can be achieved by fiddling with coding at a strategic level and setting the global healthcare system up such that a pandemic can be conjured numerically at will when the conditions are right.

But that’s not the end of it…

When Death Isn’t Enough

I think we need to grab a cuppa and turn back to that man Hope-Simpson. Here’s some of what he says on pages 206 - 208:

Some physicians in the eighteenth century paid particular attention to the mortality caused by epidemics of influenza. They noticed that not all influenzal outbreaks caused an increase in deaths over what would have been expected at the time of year, and indeed some epidemics were associated with a reduced mortality, as we shall see later.

The essay published by a Medical Society in Edinburgh describing the 1732-33 epidemic considered that the disease was not of itself fatal, " ... but it swept away a great number of poor old consumptive people, and of those who were much wasted by other distempers."

Huxham commented that the 1743 epidemic " ... although exceedingly common far and near, was fatal to few." Sir George Baker writes about the very widespread epidemic of 1762:

In this city [of London], if the public records can be trusted, the burials during the prevalence of the disease did not much exceed the average. It is remarkable that at Manchester fewer than usual died when it prevailed. At Norwich, on the contrary ... a much greater number fell victims than were destroyed by a similar pestilence in 1733, or by the more severe visitation, called Influenza, in 1743. (p. 76)

The 1775 epidemic was also reputed to have had a low mortality. Fothergill remarked:

Perhaps there is scarcely an instance to be met with, of any epidemic disease in the city [London], where so many persons were seized, and in so short a time, and with so little comparative mortality. (p. 88)

Dr. Daniel Rainey was the physician in charge of the House of Industry in Dublin, an institution founded for the suppression of beggars and sturdy vagabonds, containing 367 paupers ranging in age from 12 to 90 years. More than 200 of them were attacked by the 1775 influenza, yet the governors of the institution reported that fewer had died during the epidemic than during any similar space of time since its foundation (p. 115).

The next considerable influenza epidemic, that of 1782, was investigated by the London College of Physicians, which reported that few had died except the aged, the asthmatic, and the debilitated (pp. 163-164).

Perhaps the most interesting study from the mortality of 1837 comes from Dr. William Heberden, Jr., son of the Heberden quoted earlier in this chapter. Table 17.1, based on his table reproduced in Thompson's Annals (p. 340), compares the weekly burials with the christenings. In column 4 I have substituted the ratio of burials to christenings in place of his convention of relating burials to four christenings. The impact of influenza on the general (column 3) and specific (column 5) mortality is clear, and the age-specific figures emphasize the terminal role of influenza in the aged. It justifiably earned its name as "the old person's friend."

Well, that’s gone and torn it!

In this 17th chapter Hope-Simpson details epidemics that were clearly fatal as well as those that were most certainly not. But this is only the beginning of our journey into the heart of the paradox; for influenza is not the only lurgy lurking during the winter months. The rise in fungal spores during the late autumn triggers a raft of unpleasantness among the susceptible; and in the past elevated levels of air pollution in dwellings from fires, hearths, candles, ovens and oil lamps will have played their part as well as the cold and damp; not to mention malnutrition and horrid lurgies. Indeed so:

Much earlier, Collins had shown, as had been reported in previous centuries, that excess deaths during influenza epidemics were not confined to persons suffering from respiratory diseases, but were also to be found in groups suffering from non-respiratory illness. Housworth and Langmuir concluded that computation of excess deaths attributable to influenza are best based on the mortality from all causes rather than solely on those attributed to influenza or to influenza plus all pneumonias as in some of Frost's studies.

And I thought analysing COVID data was tricky! If I were to boil these quotes down into a teaspoon of an idea I would suggest we are looking at susceptibility of a population as the key governor of influenzal mortality. As Hope-Simpson puts it, “In some such parishes we had evidence that a lethal illness had attacked the parish community in the recent past and culled the aged and infirm who would otherwise have succumbed to influenza.”

Something else to consider while we’re at it:

Surprisingly few of the parishes demonstrated this seasonal swing in mortality in previous centuries, possibly because deaths from non-respiratory illnesses in the warmer months matched those caused by respiratory illnesses in the colder months. Dysentery, typhus, typhoid, plague, smallpox, and other ailments now uncommon must have caused many deaths in the summer during any 10-year period (page 222).

That was an eye-opener for me since I’ve accustomed myself to the regular seasonal pattern for respiratory death after programming my brain with time series after time series from 1920 onward (or thereabouts). But the genii doesn’t ever go back in the bottle: our monkey minds will already be asking just how much of that seasonal death swing can be attributed to influenza proper rather than other factors; and not just pathogenic neither: what influence does healthcare provision (or the lack of it) have? And what might be happening in care homes, and care of the elderly wards that ideally should… or shouldn’t? And how about those seasonal vaccination programmes of dubious efficacy: could they be the hidden driver behind seasonal respiratory death?

Suddenly it’s all gone very murky, and that’s before we start down the hairy path of attributing cause; and then there’s the spectre of coding death under WHO regulations and guidance. As if that wasn’t enough to contend with we also have to consider influences arising from the quirky processing of death certificates by the Office For National Statistics.

A Depressing Mountain

I’m pretty sure our raft of contentious issues surrounding influenza doesn’t stop there, and confess that all this generates a mountain of a challenge that depresses me. The good news is that Mrs Dee has perfected her recipe for gluten free all-butter Viennese fingers with dark chocolate dipped ends, and my local Waitrose now sells three varieties of Grumpy Mule coffee. Then there’s the prospect of using the fabulous new stoneware mug given to me for Christmas by my niece (who knows me inside out). These tools might make it possible to fathom something with numbers!

In the next article I’ll discuss the public domain data I’ve managed to gather and we’ll take it from there…

Kettle On!

Great subject.

For anyone interested, it has also been covered in detail by Profs Henegan and Jefferson in their Trust the Evidence series aptly named the 'Fword'. This made interesting background reading (like Hope Simpson) and covered a lot of the work from the Common Cold Research unit at Salisbury. What struck me was that whilst there are ILI (nfluenza like illnesses) that produce flu like symptoms, there are many agents that can cause them. And I recall no cause whatsoever can be found in about 20% of symptomatic cases....So when is 'flu' actually flu??

In challenge studies with the good old Rhinovirus, quite often people just did not get infected no matter how much snot and spittle was forced upon them! And in others, like you mention, spontaneous outbreaks occured at ice stations where people had been isolated for months.

It's not surprising that respiratory virus studies always throws up a can of worms. With 'flu' it seems we don't really know what it is, who is susceptible or how it is actually transmitted. But that doesn't deter the epidemiological modellers.

As an aside, I do hope you will be able to look at the data regarding the effectiveness of the 'flu' vaccine.

As ever, thanks for all your hard work, and I look forward to the next installment.

Glad to see you're getting into this topic, and with the H/S book

1) I'm not sure I would say "we have the WHO interfering with how we Brits go about counting those counts." The Brits' (and the Americans and a whole lot of other countries) willingly participate in the WHO, adopt the ICD, conform to disease surveillance directives, etc. Regarding flu, one of the GISRS centers is in London and the World Influenza Centre was established in London in - surprise! - 1918: https://www.woodhouse76.com/p/who-and-the-flu-re-do

2) As a general point regarding "seasonal waves," I found when looking at/plotting as a time series NYC daily death records from 1914-1919 that seasonal variation is not all that exaggerated. There is also some suggestion that death record keeping used to fall off at the end of the year (probably due to holidays) and that the January spike in death records is a reporting artifact. I'm very suspicious of the records in 1918 and have wondered to myself if countries involved in WWI basically put solider battlefield deaths into the fall 1918 curves - and that is one reason (among others) for the simultaneous spikes in October 1918.

3) You may know that my view is the flu shot and other "preventative treatments" are basically what make winter respiratory illnesses worse. This article is linked in mine above but ICYMI: https://totalityofevidence.substack.com/p/1900-prophylaxis-of-grippe