So far in this series I’ve presented evidence of a lagged correlation between bed loss and excess all cause and non-COVID death and we’ve seen substantial decline in bed occupancy at the onset of the first wave. Arguably more surprising than lowered occupancy was the discovery of a rapid and most substantial decline in bed availability which indicates managed withdrawal of beds at a time when computer simulations at Imperial College were predicting an incoming mega-wave of seriously sick folk. Wacko is the word!

A searching question that needs a decent answer is why did large numbers of beds get removed from service at a most critical time? When I say ‘large’ I mean gigantic, with an estimated 3,360,266 cumulative bed days withdrawn because of COVID-driven management policies.

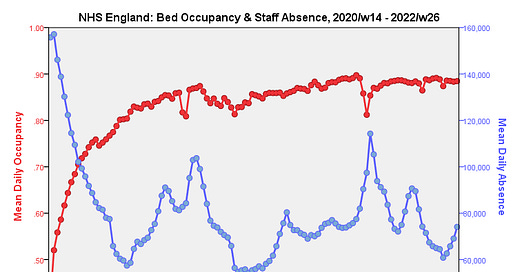

Beds don’t take care of themselves so if staff levels drop beds will be closed in order that units remain within requirements for safe nurse to patient ratios. Thus loss of staff (either through genuine sickness or a positive test result) at the height of the pandemic may well have driven planned bed closure. That’s a logical assumption for sure but does the data support such thinking? I guess we better get that kettle on, put some toast under the grill and go find out…