Excess Death Figures: Further Considerations (part 4)

Excess death is used to assess the impact of COVID, government policies and COVID therapies but this method is brimming with issues. In this article I compare five different methods

In part 3 of this series I conjured a simple ARIMA model that predicted the number of weekly non-COVID deaths for the period 2020/w1 – 2022/w46 occurring in fair England using historic data for 2014/w23 – 2019/w52, this being date of death (DOD) data rather than the usual date of registration (DOR) data. All ICD-10 chapters apart from XXII (codes for special purposes) were combined since this chapter is where the emergency use COVID-19 codes lie. At this stage quasi decadal age groups were also combined to keep things nice and simple, thus we are looking at population level sets of curves. I mentioned that my sea green predictions generally floated above observed weekly counts and thus we must expect excess death to wander down into negative values.

In this episode I am going to present a slide showing five different methods of deriving excess death so we may see for ourselves just how much these are dependent on the exact details of derivation. I am hoping readers will come away with the take home message that no single source of figures can be considered authoritative or truthful in an absolute sense, for results are very much dependent on methodology.

Some Definitions For Starters

It would be handy if folk understood what they are about to see, so I’ll start by stating that two different datasets were used, these being the DOD dataset procured by Joel Smalley and the DOR dataset downloaded from ONS.

The DOD dataset was subject to ARIMA time series analysis which produced the predicted values plotted in part 2, these being used for the baseline in the derivation of excess deaths (excess deaths = observed counts – baseline counts). Keep an eye out for the green line!

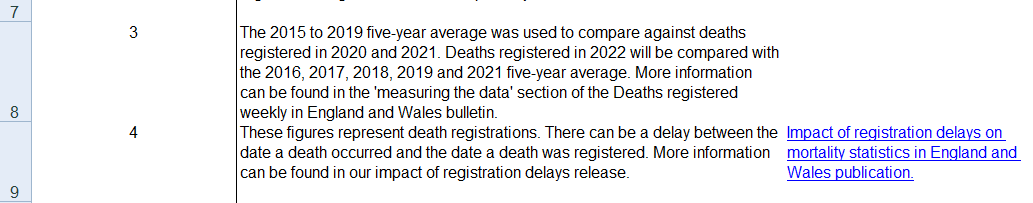

The DOD dataset was also subject to the ONS method of using prior 5-year means for the baseline, with the period 2015 – 2019 being used as the reference for years 2020, 2021 and 2022 to avoid bias arising from the pandemic itself as well as the pandemic response, whether policy outfall or vaccination outcome. The ONS do something odd in this respect since they start out by using the baseline reference period of 2015 – 2019 for both 2020 and 2021 but flip to using the years 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021 as the baseline reference for 2022. Here’s them saying so in a spreadsheet entitled publicationfileweek522022.xlsx:

If we can consider 2021 to be a ‘normal’ year for death then there isn’t a problem, but I’m not totally happy doing this just yet so I opted for caution in using 2015 – 2019 as the reference period (my ‘triple jumper’). Later on I present the results of both approaches so we may see what impact this makes, but for the time being keep an eye out for the red line.

One of the criticisms of the prior 5-year mean method is that the population doesn’t stay still, so the third method I shall present is standardised excess deaths using ONS mid year estimates for 2020 as the reference population. Keep an eye out for the orange line.

For the fourth and fifth methods I derived excess and standardised excess deaths for the DOR dataset as used by the ONS in official declarations – keep an eye out for the blue lines.

Hopefully we’re all on board, settled down and strapped in, so I shall release the crayons!